Share This Publication

Issue Brief 88 - When to Adapt: Ensuring Evidence-Based Treatments Work for Children of Diverse Cultural Backgrounds

September 8, 2023

When to Adapt:

Ensuring Evidence-Based Treatments Work for Children of Diverse Cultural Backgrounds

Approximately one in six children across the United States have a diagnosable mental health condition and roughly half report not being able to access mental health treatment.1 There are significant disparities in access to treatment with Black and Hispanic children with mental health conditions reporting approximately half as many visits to mental health providers as White children.2 When children do receive treatment, the type, quality, and effectiveness of services varies considerably.

Evidence-based treatments (EBTs) are treatments that have undergone extensive research and have been found to be effective. A number of EBTs have been developed for children and adolescents with behavioral health concerns. Though many EBTs have been found to be effective with diverse populations, clinicians may question whether the EBTs they provide should be adapted to meet the needs or preferences of children and families from diverse backgrounds. However, clinicians must balance the potential benefits of adaptations with maintaining fidelity to the core EBT components that are associated with improved child outcomes.

This Issue Brief describes what is known about making adaptations to EBTs for diverse populations and provides recommendations for clinicians on when and how to make these decisions.

EBTs are Generally Effective with Diverse Populations

Most research indicates that EBTs are generally effective for children from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds or, in some instances, can even be more effective.3-5 Several EBTs currently being delivered in Connecticut have been tested and shown to be effective for diverse populations, including Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS),6,7 Modular Approach to Therapy for Children with Anxiety, Depression, Trauma, or Conduct Problems (MATCH-ADTC),8,9 and Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT).10,11 Further, research conducted by CHDI with 46,399 children in Connecticut has shown that the use of EBTs has been associated with reductions in outcome disparities by race/ethnicity; for example, Black and Latinx children showed greater improvements when receiving EBTs compared to usual care than did White children.12

Despite this, it is important to note that some studies of EBTs have not included sufficient representation of diverse youth based on population estimates. For example, though those identifying as White or Black/African American have typically been well represented in studies on TF-CBT, some studies have included fewer individuals identifying as Hispanic/Latino, Asian, or Native American/Alaskan Native than would be expected based on their representation in the broader population.10 Further, in studies of EBTs, analyses are typically not conducted to examine if there are group differences in outcomes based on cultural background.13 This may be due to the lack of significant representation of those from diverse cultural backgrounds in the studies or due to the study authors choosing not to explore cultural group differences in their analyses.

Research Shows that Clinicians are Adapting EBTs to Address Cultural Factors

Terms used to describe changes to interventions vary in the literature, and may include “adaptation,” “tailoring,” “modification,” and “personalization.”14 Here, we use the term “adaptation” to refer to any change made to an intervention. Increasing attention has been given to cultural adaptations, defined as changes to an intervention that “consider language, culture, and context in such a way that it is compatible with the client’s cultural patterns, meanings, and values.”15

Research suggests that EBTs for children are being adapted by clinicians in day-to-day practice.16 Data from clinicians collected by CHDI found that the majority of clinicians make adaptations to EBTs based on the identity (i.e., race, gender, religion, disability, and immigration status) of the child with whom they are working. Further, recent global systematic reviews have found the need to address cultural factors to be among the most common reasons for adaptations to EBTs, with a review of evidence-based public health interventions finding this to be the most common reason for adaptation17 and a review of EBTs for children and adolescents who experienced trauma finding this to be the second most common reason for adaptation.18

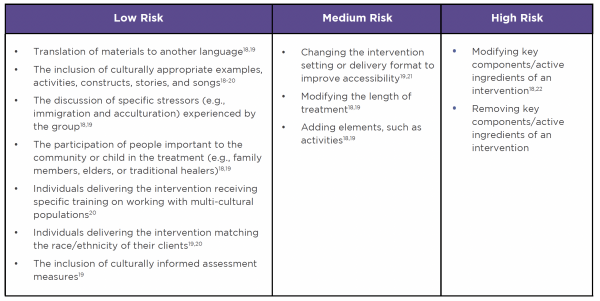

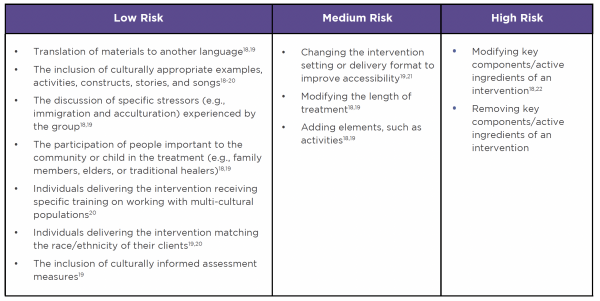

When serving diverse clients, clinicians and researchers must balance the potential benefits of adaptations with maintaining fidelity to the core EBT components so as not to negatively impact child outcomes. Table 1 includes examples of cultural adaptations that have been made to behavioral health-focused EBTs for children and adolescents and their approximate risk to fidelity:

Table 1: Risk to Fidelity of Common EBT Adaptations

Though some studies have shown that interventions that have been adapted to address cultural factors result in positive outcomes for children,18 a synthesis of studies found that “randomized trials comparing treatments that differ only in terms of cultural elements [found] no overall effects for cultural tailoring.”23 In one notable exception, a positive treatment effect was seen for the cultural adaptation 12 months post-treatment, but was not seen immediately post-treatment or three months post-treatment.4 In some instances, cultural adaptations may have negative effects on outcomes, as they may interfere with the “active ingredients” of an intervention (i.e., the trauma narrative or psychoeducation in TF-CBT and CBITS).20,22,24

Careful Consideration is Needed When Adapting EBTs

Though adaptations may not always have a positive effect on outcomes, there may be instances where these are deemed beneficial by clinicians. For example, a clinician working with a diverse population may consistently notice that certain intervention components or examples are not culturally appropriate and may be interfering with treatment progress. Further, a clinician may be working with a child and/or family who have specific preferences related to their cultural identity that impact initial engagement or how treatment is delivered over time. In both instances, a clinician may determine that an adaptation is justified, as not adapting could interfere with treatment efficacy or acceptability.

If a clinician determines an adaption is needed, they must determine what they need to adapt. This may include adapting specific components of an intervention or adapting how the intervention is delivered (see Table 1). Care should be taken not to adapt in a way that interferes with the “active ingredients” of an intervention, such as those in the “High Risk” column above. If “high-risk” adaptations are being considered, they should ideally be made in conjunction with the treatment developers or expert trainers.

Recommendations to Guide Adaptations of EBTs for Diverse Populations

When providing EBTs, clinicians should keep in mind that EBTs have generally been found to work equally well for children of diverse cultural backgrounds, though not all EBTs have been studied with children from diverse backgrounds. However, adaptations may be helpful or desired based on the clinician’s experience, child/family preference, or other factors. In instances where adaptations are being considered, it is important to:

- Identify and protect the core components of the EBT: Consult EBT manuals to determine what the “active ingredients” or core components of the intervention are before making adaptations, as the evidence indicates that changes should not be made to these components.

- Track child progress to ensure the adaptation is beneficial: Understand that when deciding to adapt an intervention, clinicians are hypothesizing that the adaptation will be beneficial for the child. This hypothesis should be tested, as not all adaptations will result in better outcomes, and some may result in worse outcomes for children. To reduce the potential that adaptations will not be effective, child progress can be tracked at each session, such as by using a measurement-based care approach.

- Apply a framework to guide adaptation decisions: Consider the use of a framework if your organization is planning an adaptation of a particular intervention to meet the perceived needs of a group of children. Though few frameworks currently exist on how to adapt EBTs that are specifically targeted to children and adolescents who experience behavioral health concerns, frameworks for adapting other forms of EBTs are available that may be applied to this population.25,26 One scoping review found 11 key steps across frameworks that should be considered when making adaptations. The steps included (1) assessing the community, (2) understanding the intervention, (3) selecting the intervention to be adapted, (4) consulting with experts, (5) consulting with stakeholders, (6) deciding what needs adaptation, (7) adapting the original program, (8) training staff, (9) testing the adapted materials, (10) implementing the adaptation, and (11) evaluating the adaptation.25

This Issue Brief was prepared by Brittany Lange, DPhil, MPH (CHDI); Jason Lang, PhD (CHDI); and Stan Huey, PhD (University of Southern California). For more information, visit www.chdi.org or contact Brittany Lange at blange@chdi.org.

References

- Whitney DG, Peterson MD. US national and state-level prevalence of mental health disorders and disparities of mental health care use in children. JAMA Pediatrics 2019; 173(4): 389-91.

- Marrast L, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S. Racial and ethnic disparities in mental health care for children and young adults: A national study. International Journal of Health Services 2016; 46(4): 810-24.

- Deblinger E, Mannarino AP, Cohen JA, Steer RA. A follow-up study of a multisite, randomized, controlled trial for children with sexual abuse-related PTSD symptoms. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2006; 45(12): 1474-84.

- Huey Jr SJ, Park AL, Galán CA, Wang CX. Culturally responsive Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for ethnically diverse populations. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 2023; 19: 51-78.

- Huey Jr SJ, Henggeler SW, Rowland MD, et al. Multisystemic Therapy effects on attempted suicide by youths presenting psychiatric emergencies. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2004; 43(2): 183-90.

- Jaycox LH, Kataoka SH, Stein BD, Langley AK, Wong M. Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools. Journal of Applied School Psychology 2012; 28(3): 239-55.

- The California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare. Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS). 2019. https://www.cebc4cw.org/program/cognitive-behavioral-intervention-for-trauma-in-schools/.

- Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL, Park AL, et al. Child STEPs in California: A cluster randomized effectiveness trial comparing modular treatment with community implemented treatment for youth with anxiety, depression, conduct problems, or traumatic stress. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 2017; 85(1): 13-25.

- The California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare. Modular Approach to Therapy for Children with Anxiety, Depression, Trauma, or Conduct Problems (MATCH-ADTC). 2019. https://www.cebc4cw.org/program/modular-approach-to-therapy-for-children-with-anxiety-depression-trauma-or-conduct-problems/.

- The California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare. Trauma-Focused Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT). 2019. https://www.cebc4cw.org/program/trauma-focused-cognitive-behavioral-therapy/.

- Thielemann JFB, Kasparik B, König J, Unterhitzenberger J, Rosner R. A systematic review and meta-analysis of Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for children and adolescents. Child Abuse & Neglect 2022; 134: 105899.

- Lang JM, Lee P, Connell CM, Marshall T, Vanderploeg JJ. Outcomes, evidence-based treatments, and disparities in a statewide outpatient children’s behavioral health system. Children and Youth Services Review 2021; 120: 105729.

- Chorpita BF, Weisz JR, Daleiden EL, et al. Long-term outcomes for the Child STEPs randomized effectiveness trial: A comparison of modular and standard treatment designs with usual care. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 2013; 81(6): 999-1009.

- Bennett SD, Shafran R. Adaptation, personalization and capacity in mental health treatments: A balancing act? Current Opinion in Psychiatry 2023; 36(1): 28-33.

- Bernal G, Jiménez-Chafey MI, Domenech Rodríguez MM. Cultural adaptation of treatments: A resource for considering culture in evidence-based practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 2009; 40(4): 361.

- Lau A, Barnett M, Stadnick N, et al. Therapist report of adaptations to delivery of evidence-based practices within a system-driven reform of publicly funded children’s mental health services. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 2017; 85(7): 664.

- Escoffery C, Lebow-Skelley E, Haardoerfer R, et al. A systematic review of adaptations of evidence-based public health interventions globally. Implementation Science 2018; 13(1): 1-21.

- Lange BCL, Nelson A, Lang JM, Stirman SW. Adaptations of evidence-based trauma-focused interventions for children and adolescents: A systematic review. Implementation Science Communications 2022; 3(1): 1-21.

- Arora PG, Parr KM, Khoo O, Lim K, Coriano V, Baker CN. Cultural adaptations to youth mental health interventions: A systematic review. Journal of Child and Family Studies 2021; 30(10): 2539-62.

- Huey Jr SJ, Polo AJ. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for ethnic minority youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology 2008; 37(1): 262-301.

- Stewart RW, Orengo-Aguayo R, Wallace M, Metzger IW, Rheingold AA. Leveraging technology and cultural adaptations to increase access and engagement among trauma-exposed African American youth: Exploratory study of school-based telehealth delivery of Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 2021; 36(15-16): 7090-109.

- Kliewer W, Lepore SJ, Farrell AD, et al. A school-based expressive writing intervention for at-risk urban adolescents’ aggressive behavior and emotional lability. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology 2011; 40(5): 693-705.

- Huey SJ, Jones EO. Improving treatment engagement and psychotherapy outcomes for culturally diverse youth and families. Handbook of Multicultural Mental Health 2013: 427-44.

- Stirman W, Shannon, Baumann AA, Miller CJ. The FRAME: An expanded framework for reporting adaptations and modifications to evidence-based interventions. Implementation Science 2019; 14(1): 1-10.

- Escoffery C, Lebow-Skelley E, Udelson H, et al. A scoping study of frameworks for adapting public health evidence-based interventions. Translational Behavioral Medicine 2019; 9(1): 1-10.

- Movsisyan A, Arnold L, Evans R, et al. Adapting evidence-informed complex population health interventions for new contexts: A systematic review of guidance. Implementation Science 2019; 14(1): 1-20.