Issue Brief 85: Making Measures Matter

Measurement-based care (MBC) is the routine use of symptom or outcome measures for collaborative decision-making and treatment planning. It is considered an evidence-based practice (EBP) because it has been shown to improve health outcomes. For example, healthcare providers have used MBC to improve physical health outcomes for many years, including regularly obtaining blood pressure readings or lab results for cholesterol and diabetes. These measures provide touchpoints for how care is progressing and whether changes in the care plan may be helpful.

Over the last decade, MBC has been increasingly studied and applied in behavioral health, with positive results, including with children and families. Improvements in care are especially needed given the longstanding yet worsening children’s behavioral health crisis, including the impact of COVID-19,1 resulting in a greater need for children’s behavioral health services and a strained behavioral health workforce.2 While EBPs are an effective strategy for improving behavioral health care and Connecticut has been a leader in making EBPs available for children with specific needs, more generalizable and efficient models are needed to improve access to EBPs. MBC is an EBP that can be implemented with relatively minimal investment and used for any population or setting.

This Issue Brief describes how MBC can enhance family-centered care, reduce costs, and improve outcomes in children’s behavioral health services.

MBC improves behavioral health care quality and outcomes and reduces cost

With MBC, brief standardized measures are used to help the clinician, child, and family communicate about treatment goals, progress, and satisfaction with services. With a shared understanding and language grounded in data and patient-centered experiences, treatment strategies can be adjusted in “real-time,” resulting in better outcomes. Measures of behavioral health concerns (e.g., Personal Health Questionnaire-9; Behavior and Feelings Survey) are completed at regular intervals and as often as every session. Clinicians review measure results with clients and collaboratively determine the next step in treatment, which may include maintaining course or exploring different treatment options (e.g., session frequency, goal change, skill development, change in level of care).

The use of collaboration, transparency, personalized monitoring, and feedback well-positions MBC to promote equitable outcomes across diverse racial groups.3 A recent review of 58 studies shows that MBC improves symptom reduction and decreases the dropout rate when compared to treatment without MBC.4 MBC also enhances patient-centered care and clinical processes, such as engagement and therapeutic alliance.5 Finally, MBC may also reduce costs; for example, clinic-based providers using evidence-based treatments experienced an average cost savings of 37%6 and a 13% decrease in overall session use7 while maintaining clinical outcomes when they incorporated routine outcome monitoring and feedback in their sessions.

MBC can be implemented flexibly across diverse settings and populations

MBC is transtheoretical8, 9 and flexible enough to be used with any population, clinical concern, or setting, such as clinics, schools, or varying levels of care.10, 11 Further, MBC can complement virtually any behavioral health treatment, including usual care, EBPs, or other treatments focused on specific conditions and populations.4 Governance provided by professional standards organizations (e.g., the American Psychological Association), accreditation entities (e.g., the Joint Commission), and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services have recommended that health care systems incorporate MBC as a best practice that contributes to value-driven care.12

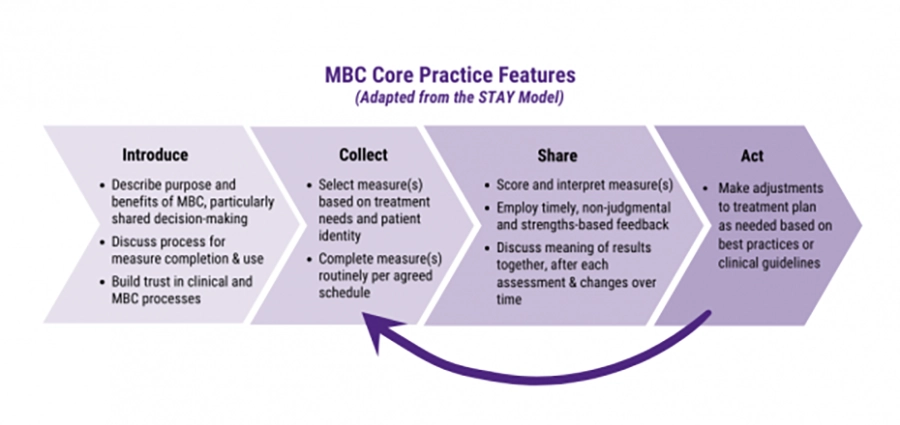

MBC implementation can range from simple to sophisticated depending on the scope of the program and resources available. Simple MBC may consist of paper-and-pencil or electronic measures completed with the clinician, who scores and interprets measures, provides feedback, engages in shared decision-making, and works with the family to integrate results into treatment planning and sessions (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

More sophisticated MBC digital platforms can routinely administer and score measures through handheld devices (cellular phones, tablets) and email links to families.13, 14 Additional features that may enhance MBC implementation include automated reminders for completing measures, advanced data tracking and reporting features for feedback and interpretation (e.g., graphs, benchmarks), and integration with electronic health records (EHRs). Basic automated scoring and graphing may also be supported with consumer software programs, such as Google Sheets or Microsoft Excel.

Providers should identify a realistic and sustainable approach for their organization, including identifying brief standardized measures that fit the needs of their population4 and workforce. Ideally, organizations that invest in more sophisticated digital user systems may want to select one that integrates with their EHR and is compatible with telehealth formats.13 Further, organizations should identify and address potential access barriers to MBC technologies, such that all families have access to MBC regardless of their technological knowledge or resources.15, 16

Behavioral health providers who are new to MBC can adjust and scale their implementation based upon available resources, level of commitment and interest, identified staff to implement, and sustainability plan. If starting small, an organization may identify a few clinicians and a supervisor to pilot a measure appropriate for their clients and program. Clinicians and supervisors will ideally develop a regular process that reviews results in the context of treatment and troubleshoot any concerns.

When effective processes are developed, organizations can expand MBC by adding more clinical teams and potentially expanding the measures available. Systems that integrate more sophisticated MBC tools (e.g., digital platforms) may involve non-clinical staff (e.g., information technology staff) to support rollout, particularly given the complexity of integrating with EHRs or other data systems. Finally, best practices that enhance engagement of racially and ethnically diverse youth in MBC are currently being developed and tested, including whether cultural adaptations are helpful; for example, the Strategic Treatment Assessment with Youth (STAY) addresses perceptual barriers to MBC with such youth.17

Efforts to advance measurement-based care in Connecticut are underway

Many of Connecticut’s child-serving behavioral health providers have experience in routinely using data from standardized measures to support treatment. For instance, the Connecticut Department of Children and Families (DCF) maintains an online Provider Information Exchange (PIE) data system for quality improvement and program evaluation for use among its contracted behavioral health providers. Some DCF-funded systems provide automated scoring and feedback reports consistent with MBC. For example, EBP Tracker was developed to support the implementation of EBPs through a collaboration with CHDI, and the Global Appraisal of Individual Needs Assessment Building System (GAIN ABS) through a partnership with Chestnut Health systems.

Many organizations and projects across Connecticut are advancing MBC right now. For example, a multi-year public-private partnership between DCF, CHDI, and Mirah was established to trial a digital provider- client user facing system, working with CHR and Clifford Beers as pilot sites. Mirah’s MBC software integrates with EHRs, sends pre-selected measures to clients and caregivers electronically via handheld devices and email, and provides actionable, instant feedback that is accessible, interpretable, and usable by clinicians in real-time.

In another local MBC initiative, Yale University researchers are partnering with West Haven and Stamford Public Schools to use the Better Outcomes Now MBC system. This pilot project, known as the Feedback and Outcomes for Clinically Useful Student Services (FOCUSS), offers training and support to school staff to collect and use brief measures to track student progress and promote shared mental health decision-making among youth, families, and school mental health staff. These and other projects will help identify successful approaches and next steps for Connecticut to further MBC implementation in the children’s behavioral health system.

Recommendations to support MBC

Connecticut has a strong foundation upon which to advance MBC in children’s behavioral health.The following recommendations will support MBC implementation and overall improvements in the children’s behavioral health system:

- The Connecticut legislature, state agencies, and other behavioral health funders should allocate financial, implementation, and technical assistance support for providers in using a range of MBC solutions. MBC quality, equity, and cost-effectiveness should be prioritized and evaluated.

- The Connecticut Department of Social Services should pursue policy and reimbursement changes that integrate MBC as one component of a value-based or alternative payment model, beginning with the most widely utilized level of care, outpatient services.

- Behavioral health provider agencies and networks should explore and pilot MBC approaches based on available resources, including selecting measures, creating an implementation plan, identifying consultation needs and support, and promoting use of an ongoing quality improvement approach.

- Researchers and intermediary organizations should continue to evaluate the effectiveness of MBC, particularly in child-serving systems with a focus on equity and the potential differences between simple and sophisticated MBC implementation.

This Issue Brief was prepared by Jack Lu, PhD, Christine Hauser, LCSW, LADC, and Jason Lang, PhD.

References

-

The White House. (2022, May 31). FACT SHEET: Biden-Harris administration highlights strategy to address the national mental health crisis. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/05/31/fact-sheet-biden-harris-administration-highlights-strategy-to-address-the-national-mental-health-crisis/

-

National Council for Mental Wellbeing. (2021, September). Impact of COVID-19 on behavioral health workforce. https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/NCMW-Member-Survey-Analysis-September-2021_update.pdf

-

Barber, J., & Resnick, S. G. (2022). Collect, share, act: A transtheoretical clinical model for doing measurement-based care in mental health treatment. Psychological Services. Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/ser0000629

-

de Jong, K., Conijn, J. M., Gallagher, R. A. V., Reshetnikova, A. S., Heij, M., & Lutz, M. C. (2021). Using progress feedback to improve outcomes and reduce drop-out, treatment duration, and deterioration: A multilevel meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 85, 102002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102002

-

Tepper, M. C., Ward, M. C., Aldis, R., Lanca, M., Wang, P. S., & Fulwiler, C. E. (2022). Toward population health: Using a learning behavioral health system and measurement-based care to improve access, care, outcomes, and disparities. Community Mental Health Journal, 1-9. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-022-00957-3

-

Delgadillo, J., Overend, K., Lucock, M., Groom. M., Kirby, N., McMillan, D., Gilbody, S., Lutz, W., Rubel, J. A., & de Jong, K. (2017). Improving the efficiency of psychological treatment using outcome feedback technology. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 99, 89-97. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2017.09.011

-

Janse, P. D., De Jong, K., Van Dijk, M. K., Hutschemaekers, G. J. M., & Verbraak, M. J. P. M. (2017). Improving the efficiency of cognitive-behavioural therapy by using formal client feedback. Psychotherapy Research, 27(5), 525-538, https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2016.1152408

-

Jensen-Doss, A., Douglas, S., Phillips, D. A., Gencdur, O., Zalman, A., & Gomez, N. E. (2020). Measurement-based care as a practice improvement tool: Clinical and organizational applications in youth mental health. Evidence Based Practice in Child Adolescent Mental Health, 5(3): 233–250. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33732875/

-

Scott, K. & Lewis, C. C. (2015). Using measurement-based care to enhance any treatment. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(1), 49-59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.01.010.

-

Childs, A. W. & Connors, E. H. (2021). A Roadmap for measurement-based care implementation in intensive outpatient treatment settings for children and adolescents. Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 6(3), 393-409. https://doi.org/10.1080/23794925.2021.1975518

-

Lewis, C. C., Boyd, M., Puspitasari, A., Navarro, E., Howard, J., Kassab, H., Hoffman, M., Scott, K., Lyon, A., Douglas, S., Simon, G., & Kroenke, K. (2019). Implementing measurement-based care in behavioral health: A review. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(3), 324–335. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3329

-

Wright, C. V., Goodheart, C., Bard, D., Bobbitt, B., Butt, Z., Lysell, K., McKay, D., Stephens, K. (2020). Promoting measurement-based care and quality measure development: The APA mental and behavioral health registry initiative. Psychological Services, 17(3), 262-270. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000347

-

Chiauzzi E. & Wicks, P. (2021). Beyond the therapist’s office: Merging measurement-based care and digital medicine in the real world. Digital Biomarkers, 5(2), 176-182. https://doi.org/10.1159/000517748

-

Murphy, J. K., Michalak, E. E., Liu, J., Colquhoun, H., Burton, H., Yang, X., Yang, T. Wang, X., Fei, Y., He, Y., Wang, Z., Xu, Y., Zhang, P., Su, Y, Huang, J., Huang, L., Yang, L., Lin, X., Fang, Y., Liu, T., … Chen, J. (2021). Barriers and facilitators to implementing measurement-based care for depression in Shanghai, China: A situational analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 21(1), 1-35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03442-5

-

Liu, F. F., Cruz, R. A., Rockhill, C. M., & Lyon, A. R. (2019). Mind the gap: Considering disparities in implementing measurement-based care. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 58(4), 459-461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2018.11.015

-

Sisodia, R. C., Rodriguez, J. A., & Sequist, T. D. (2021). Digital disparities: lessons learned from a patient reported outcomes program during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 28(10), 2265-2268. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocab138

-

Connors, E. H., Arora, P. G., Resnick, S. G., & McKay, M. (2022). A modified measurement-based care approach to improve mental health treatment engagement among racial and ethnic minoritized youth. Psychological Services. Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/ser0000617