Issue Brief 84: Modernizing Outpatient Behavioral Health for Children

Access to children’s behavioral health services has been a longstanding challenge for many families. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, approximately half of all children with behavioral health conditions did not receive treatment or adequate care.1 Access to services is worse for children of color; for example, a recent study indicated that approximately 65% of Black and 62% of Latinx adolescents with depression received no treatment.2 The COVID-19 pandemic has placed an additional burden on healthcare systems, including an emerging crisis with the behavioral healthcare workforce and infrastructure3 that results in longer waitlists for treatment.4 Children are experiencing higher rates of anxiety, depression, and stress,5 and longstanding health disparities for children of color have worsened.6

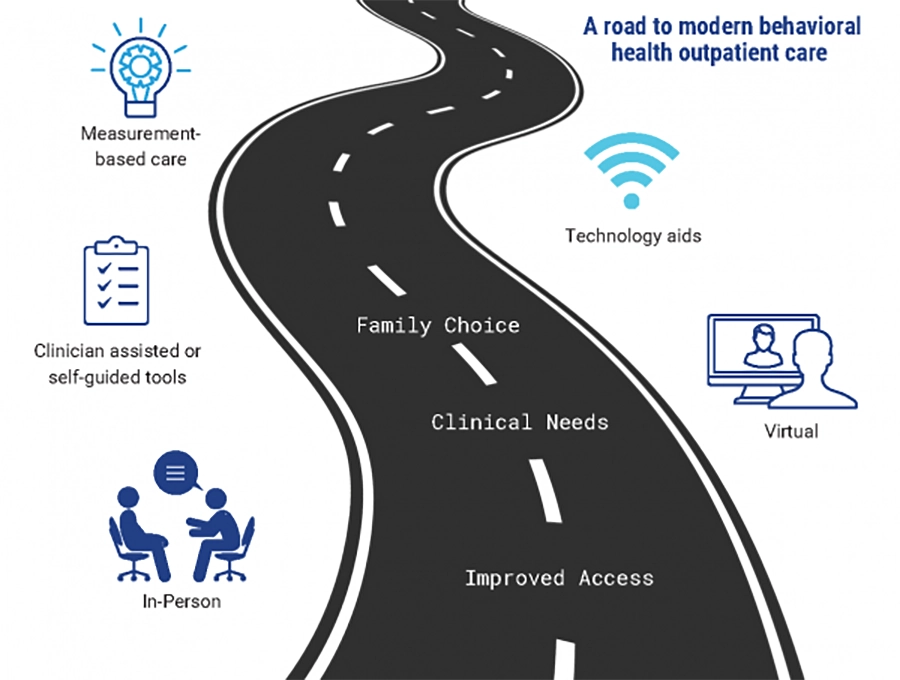

Contemporary innovations that combine in-person and virtual sessions with self-service, low-touch, and technological supports may uniquely benefit children’s outpatient behavioral healthcare systems. This Issue Brief describes how modernizing children’s outpatient care can reduce barriers and expand families’ access to behavioral health services.

Accessing behavioral health services is a persistent problem for many families

Though outpatient services remain the primary entry point to behavioral healthcare for most children, many families have trouble finding and maintaining clinic-based services. It can be challenging to find a local provider available during a mutually convenient time with expertise in the child’s specific needs and who accepts the family’s insurance. Maintaining clinic-based treatment involves additional barriers, such as transportation, repeated time away from work or childcare responsibilities, the perceived stigma associated with going to a mental health clinic, and limited flexibility with scheduling.

There is also an increasing shortage of behavioral health clinicians to meet the growing needs of children and families, resulting in reduced access and longer waits, particularly for children with less acute needs. The recent scaling up of telehealth during the pandemic has helped address some, but not all, of these barriers.

Modern healthcare approaches improve access to outpatient care

Outpatient behavioral healthcare has evolved significantly in the past decade, particularly in response to COVID-19. Telehealth services (e.g., virtual, phone) are more common than ever. There are also an increasing number of low-touch supports (e.g., clinician-assisted or self-guided apps, workbooks, or activities), measurement-based care (MBC) approaches, and technology-assisted services that promote a more flexible, efficient, and family-centered approach to behavioral health services. Many of the building blocks for these modern approaches already exist within the children’s behavioral healthcare system.

In-person clinic-based behavioral health services are widely available, even if waitlists exist. In-person services are especially needed for some populations, including families without technology access, those without a private or safe location at home for telehealth, and younger children. Additionally, in-person services may be more effective for children with specific clinical concerns, such as ongoing safety risks, hygiene concerns, or indications of substance use. The pandemic spurred a rapid increase in telehealth services that supports a hybrid healthcare model integrating telehealth and in-person services. Most clinics and provider networks that traditionally relied on in-person therapy now also offer telehealth options.

While research predating the pandemic has shown that telehealth is as effective as in-person treatment,7,8 the use of telehealth over the past two years in Connecticut and nationally has demonstrated that it is feasible on a large scale and has numerous benefits such as eliminating transportation barriers, improving attendance, and reducing financial risks to providers due to fewer no-show appointments. Telehealth can improve coordination of care for youth and families since it is easier for multiple providers and the family to meet virtually than in-person and provides families with access to care beyond their local community.

Flexible supports and data insights enhance in-person and virtual care

Recent developments in low-touch clinician-assisted or self-guided services and supports can complement in-person and telehealth services to efficiently reach more children. These supports are particularly beneficial for children with milder symptoms or who are in remission but not ready to end treatment or those who cannot attend regular clinic-based or telehealth treatment sessions.

These low-touch supports could include single session (or very brief) interventions,9 group interventions, and services via mobile apps, websites, or workbooks that offer self-guided or clinician-assisted therapeutic skill reinforcement or practice. Such apps can improve treatment quality10 and reduce the costs of care11 while creating more efficiencies and options for families to meet the range of children’s behavioral health needs. These services require less time with a clinician, can be scaled up at low costs, and increase access for children with less acute needs.

MBC is the regular use of outcome data by clinicians to inform treatment strategies and progress. MBC is an evidence-based practice12 that can improve outcomes, enhance engagement, and support a more flexible approach to treatment (e.g., determining when virtual or clinician-assisted services could be helpful). MBC can be used by any clinician with any child or family for any clinical concern and can be used in conjunction with any combination of in-person, telehealth, and low-touch services.

Technological advancements can support MBC, such as reducing the burden on clinicians for data collection, entry, and monitoring. Existing software platforms offer HIPAA-secure web, app, and telephonic-based methods for collecting and reporting treatment outcomes that provide real-time insights to clinicians and families. These systems provide automatic reminders and integrate with most electronic health records. Data can be collected asynchronously at convenient times with tablets or cell phones. Though particularly promising for youth preference and engagement, the effectiveness of these technologies at scale requires further study and commercial systems often have significant costs, which are not currently reimbursed through insurance.

In application, a provider equipped with this modern array of strategies will develop or use best practice guidelines to engage youth and families at the onset of and throughout treatment based on client preferences, available technological resources, clinical fit, and treatment progress. A typical treatment episode may include a combination of in-person and telehealth sessions and the use of MBC technology to monitor progress while eventually shifting to low-touch, clinician-assisted apps or workbooks as the symptoms abate. For some children with milder concerns, a single session intervention, with or without low-touch supports or brief follow-up, might be sufficient and preferred by the family.

Connecticut’s evolution in modern outpatient behavioral healthcare

Connecticut is well-positioned to integrate modern approaches to children’s outpatient behavioral health. Behavioral health providers and child-serving systems have significantly changed due to COVID-19, particularly in establishing telehealth services and reimbursement and developing approaches for triaging families for in-person or telehealth services. The State’s extension of telehealth reimbursement until June 2023 supports providers in refining, evaluating, and combining telehealth with clinic-based treatment. In addition, Connecticut has invested in robust technologies (e.g., statewide data systems) that support data collection, reporting, and quality improvement of children’s behavioral healthcare. These technologies provide a strong foundation for supporting MBC.

Additional work is needed to integrate low-touch clinician-assisted and self-guided behavioral health supports into the outpatient service array to support a more modern and flexible approach to care. While families may complete some currently non-reimbursed services as “homework” between regular therapy sessions, the State must examine policy and reimbursement issues to adequately support low-touch services as an important component of more flexible and sustainable outpatient service delivery.

Recommendations

The following recommendations will advance children’s outpatient behavioral health care in Connecticut and beyond:

1. The Connecticut legislature and Department of Social Services should ensure permanent reimbursement for telehealth and audio-only sessions.

2. The Connecticut Department of Social Services can explore changes to policy and reimbursement that support modern services that support flexible service delivery, such as the use of low-touch clinician-guided services and MBC as part of routine outpatient care.

This approach can be part of value-based or alternative payment models.

3. The State and/or researchers should develop guidelines and best practices for modernizing outpatient healthcare.

This should include how to most effectively use the range of strategies (e.g., hybrid formats, low-touch supports, MBC, technology aids, self-service tools) for various populations of children.

4. State agencies can identify new funding streams (e.g., American Rescue Plan Act investments; federal block grants, state grants) to enhance and update provider electronic health records, MBC platforms, and telehealth service delivery.

5. Behavioral health provider agencies and networks can identify current and future opportunities to move towards a modern approach, given current policy and reimbursement:

- Identify current in-person and telehealth activities that can be expanded.

- Formalize organizational policies and practice guidelines that provide stability for staff and flexibility for client preferences in utilizing a combination of in-person, telehealth, and low-touch supports.

- Ensure clinical personnel are trained in modern approaches, including matching family preferences with a range of service options.

- Invest in low-touch, low resource supports (e.g., clinician-guided or single session/brief interventions) that supplement conventional treatment.

6. State agencies and collaborators should evaluate and research the impact of modern strategies on outpatient service delivery, such as access, quality, outcomes, disparities, equity, staff morale and retention, productivity, revenue, and cost-effectiveness.

- Whitney, D. G., & Peterson, M. D. (2019). US national and state-level prevalence of mental health disorders and disparities of mental health care use in children. JAMA Pediatr, 173(4), 389-391. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5399

- SAMHSA Office of Behavioral Health Equity. (2021). Black/African American. https://www.samhsa.gov/behavioral-health-equity/black-african-american

- American Hospital Association. (2021). Fact sheet: Federal investment in behavioral health infrastructure needed to address mounting crisis. https://www.aha.org/fact-sheets/2021-05-26-fact-sheet-federal-investment-behavioral-health-infrastructure-needed

- Bebinger, M. (2021). Wait lists for children’s mental health services ballooned during COVID. https://www.wbur.org/news/2021/06/22/massachusetts-long-waits-mental-health-children-er-visits

- Jones, E. A. K., Mitra, A.K., & Bhuiyan, A.R. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on mental health in adolescents: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 18, 2470. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052470

- Lopez L, Hart L. H., & Katz, M. H. (2021). Racial and ethnic health disparities related to COVID-19. JAMA, 325(8), 719–720. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.26443

- Hilty, D. M., Ferrer, D. C., Parish, M. B., Johnston, B., Callahan, E. J., & Yellowlees, P. M. (2013). The effectiveness of telemental health: A 2013 review. Telemed J E Health, 19(6):444-54. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2013.0075

- Schaffer, C. T., Nakrani, P., & Pirraglia, P. A. (2020). Telemental health care: A review of efficacy and interventions. Telehealth and Medicine Today, 5(4). https://doi.org/10.30953/tmt.v5.218

- Schleider, J. L., & Weisz, J. R. (2017). Little treatments, promising effects? Meta-analysis of single-session interventions for youth psychiatric problems. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 56(2), 107-115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.11.007

- Bennett, S. D., Cuijpers P., Ebert, D. D., McKenzie Smith, M., Coughtrey, A. E., Heyman, I., Manzotti, G., & Shafran, R. (2019). Practitioner review: Unguided and guided self-help interventions for common mental health disorders in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry, 60(8), 828-847. doi:10.1111/jcpp.13010

- Powell, A. C., Chen, M., & Thammachart, C. (2017). The economic benefits of mobile apps for mental health and telepsychiatry services when used by adolescents. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 26(1), 125-133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2016.07.013

- Douglas, S., Jensen-Doss, A., Ordorica, C., & Comer, J. S. (2020). Strategies to enhance communication with telemental health measurement-based care (tMBC). Practice Innovations, 5(2), 143–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/pri0000119

This Issue Brief was prepared by Jack Lu, PhD and Jason Lang, PhD. For more information, contact Dr. Lu.