July 28, 2020

Many families struggle to meet basic needs such as food, stable and healthy living conditions, and access to health care. Commonly referred to as social determinants of health (SDOH), these factors – which are present for many children starting at birth – are estimated to account for 80-90% of modifiable contributors to health outcomes.2 Research has shown that SDOH, including socioeconomic inequalities,3 food insecurity,4 and poor housing quality5 are associated with mental health concerns among children, suggesting that meeting social needs will have an impact on mental health. There are also disparities in SDOH, with racial and ethnic inequities seen in poverty rates,6 housing,6 education,6 and food insecurity.7 Better integration of clinical and social services has the potential to improve children’s overall well-being and close longstanding gaps between populations.

|

What are the Social Determinants of Health? SDOH are defined as “conditions in the environments in which people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks.”1 SDOH comprise five domains:

|

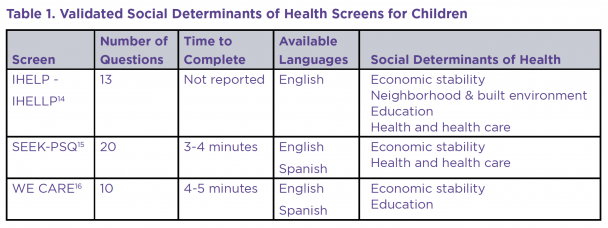

Several service sectors currently screen for SDOH and connect families to community services to meet their specific needs. Pediatric practices have significantly increased their use of SDOH screening over the last decade in an effort to increase early detection and linkage to intervention for unmet social needs.8 However, SDOH screening remains underutilized in other child-serving settings, such as schools and behavioral health.8

The COVID-19 pandemic has illuminated the presence of health disparities across the nation stemming from decades of inequities. It has also highlighted the importance of SDOH, as unemployment, food insecurity, and health concerns have increased, particularly among low-income individuals and communities of color. As Connecticut’s children return to schools, childcare, and other community settings, providers of children’s services, including behavioral health providers, have opportunities to significantly improve children’s overall health and well-being by identifying families with SDOH needs and connecting them to available services. This Issue Brief explores screening for SDOH by children’s behavioral health providers as a promising strategy for improving children’s behavioral health and wellness.

In 2014, Connecticut’s first State Health Improvement Plan (SHIP) outlined a roadmap to improve population health and health equity through partnerships between state agencies and key stakeholders. The plan included seven wide-ranging focus areas such as maternal, infant, and child health (e.g., reproductive health, pregnancy care, and child well being), environmental risk factors (e.g., air quality and healthy communities), and injury and violence prevention (e.g., unintentional injury, suicide, and community violence). The state’s SHIP 2.0 is a five-year plan that is currently under development, but anticipated to use the SDOH as the central focus of an integrated framework for achieving population health and health equity.9

Additionally, the Unite Connecticut initiative led by the Connecticut Hospital Association is a multi-year campaign to build a network of hospital, health system, and social service providers to coordinate SDOH screening and referrals.10 This network links hospital, health system, and social service provider data systems via a web portal and allows for tracking the completion of SDOH screens, the completion of referrals, and the initiation of follow-up services. Although the Unite Connecticut system may benefit people who receive care through hospitals, many children do not frequently access care through hospitals, making it important to also screen for SDOH in other settings.

Behavioral health services are ideal for SDOH screening given the strong connection between SDOH and behavioral health. Though standardized SDOH screening is less common in behavioral health settings,8 they are optimal settings for coordinating care and addressing, or connecting families to services that address unmet basic needs. For example, through the Care Coordination Program and Intensive Care Coordination Program of WrapCT, the Integrated Care for Kids model, and the Connecticut Network of Care Transformation (CONNECT), behavioral health providers aim to address client-identified needs, particularly basic needs, such as housing and food. Screening for and identifying basic needs helps to address the most critical barriers in moving the family toward their goals. By invoking family strengths, the plan of care helps to prioritize meeting basic needs first so that families can attend to behavioral and health needs with more successful and sustainable outcomes.

As SDOH screening and linkage to services becomes part of routine practice in clinical settings, several issues have been highlighted:

Despite challenges with screening and follow up, SDOH screening has shown a number of benefits. Specifically, research has shown that screening can result in increased discussions with families regarding their needs, referrals to address these needs, and the receipt of interventions targeting these needs.8 Further, recent research in pediatric practices shows that screening for SDOH in these settings, and subsequent referrals to address needs, results in improved behavioral and physical health for children.12 In order to make SDOH screening most useful, providers should consider other factors including a family’s current circumstances, strengths, and preferences for referrals, as well as the availability of resources to meet mutually identified needs.13

Connecticut is well-positioned to support SDOH screening by child behavioral health providers. Behavioral health organizations typically include a strong cadre of well-trained care coordinators working alongside behavioral health providers, and both disciplines have long histories of collaboration and extensive experience with screening and referral to services. The presence of many existing partnerships and collaboratives in children’s behavioral health has built significant capacity for disseminating new innovations. The state’s focus on SDOH in the SHIP 2.0 provides a policy platform for supporting and monitoring this work. The following recommendations can enhance Connecticut’s efforts to meet the basic needs of families:

This Issue Brief was prepared by Brittany Lange, DPhil, MPH, Senior Project Coordinator; Jack Lu, PhD, Director of Implementation; and Jason Lang, PhD, Vice President for Mental Health Initiatives. For more information, contact Brittany Lange at blange@chdi.org.

|

Brittany Lange, DPhil, MPH - Senior Associate blange@chdi.org |

|

Jack Lu, Ph.D, LCSW - Director of Implementation jlu@chdi.org |

|

Jason Lang, Ph.D - Chief Program Officer jlang@chdi.org |